The Cool White project: combating climate impacts with a coat of paint

The sun beats down on Dar Es Salaam in Tanzania, a key trading hub in the emerging economic region of East Africa. In the port city, temperatures can reach 35 degrees Celsius all year round, even in December. In certain places – house façades, for example – the thermometer can climb as high as 60 degrees. If you live or work the whole year in a building like this, how do you keep your cool?

Electronic cooling systems cost a lot of money and account for almost 20 per cent of electricity consumption and 10 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide – and the trend is upwards. But on the roof and façade of a hospital in Dar Es Salaam, there’s a clue to how simple solutions could help companies save this energy in future. In early November 2024, work began on a new venture of the Cool White project, an initiative founded by the Federation of German Wholesale, Foreign Trade and Services (BGA), the Business Scouts for Development at the German Agency for Business and Economic Development (AWE) and the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB – Germany’s national metrology institute) with support from GIZ.

Heiko Herzog is a professional painter and decorator from Germany. Trained by him and under his direction, local workers painted the hospital roof white. Why? Because the white paint is designed to reflect the light, preventing not just the roof but also the interior of the hospital from heating up. Measurements conducted by Herzog showed that the white paint reduced the temperature on the roof surface by almost 20 degrees Celsius. The hospital doctors were delighted with the immediate effects and intend to continue the measurements in future. The hospital in Dar Es Salaam is not the first building to get a coat of paint courtesy of Cool White. And if the project organisers at BGA, AWE and PTB have their way, it will not be the last.

Relieving pressure on the climate, people – and solar panels

The idea that paint can cool is not a new one: 15 years ago, Steven Chu, a winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics and energy minister in the USA at the time, proposed that all houses in the USA should be painted white as a sustainable way of keeping them cool. Projects like Cool White are now putting this idea into practice in the countries of the Global South. Cool White combats climate change and its impacts in various ways. It does not just reduce the need for cooling systems. Its cooling effect also improves the wellbeing of the people using the buildings. Doctors and patients in hospitals are not the only ones to benefit. Companies, too, especially those with employees whose work is physically demanding, such as factory workers, can ensure their productivity does not suffer. This is especially important in the light of studies warning that global work productivity could fall by 20 per cent in future due to heat.

For solar system operators, the cooling white paint has a positive side effect: initial studies indicate that photovoltaic modules achieve higher voltage when surface temperatures are reduced. This means that they are probably more efficient when mounted on surfaces treated with Cool White paint. The white paint is an example of a passive (daytime) radiative cooling material (P(D)RC).

So what’s the secret?

How the paint works (as proven)

PRC technology involves materials that cool the exterior surfaces and interior spaces of buildings without using energy. Other examples besides Cool White paint are cooling ceramics and nano-film coatings. Thanks to their optical properties, PRC materials can reflect light and simultaneously dissipate heat into outer space via what is known as the infrared atmospheric window. Theoretically, this effect can even reduce the temperature of objects to below that of their environment.

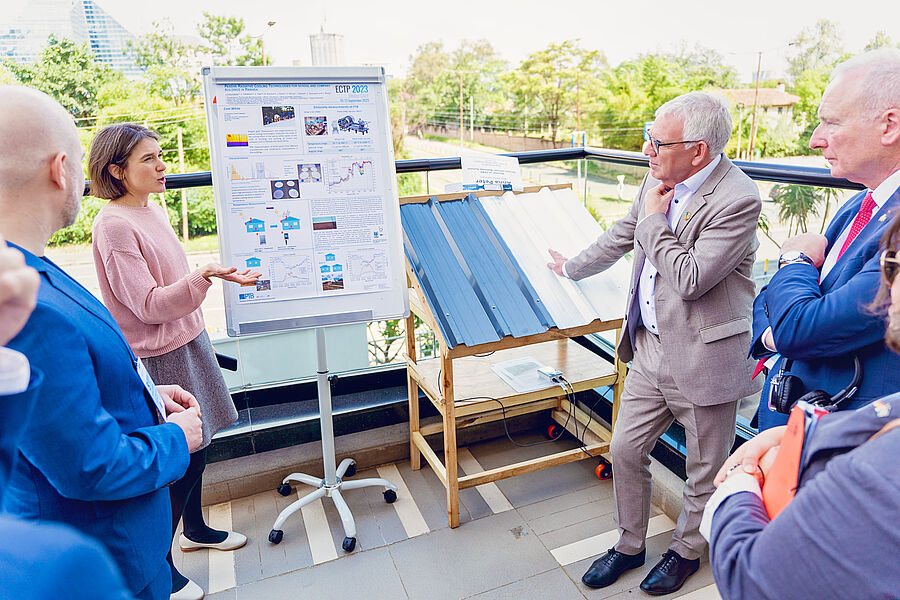

In Rwanda and South Africa, a PTB research team set out to find out whether Cool White paint could also live up to this promise. Back in 2023, master craftsman Heiko Herzog and a team of local and German painters had already painted the roofs of school and company buildings white in Rwanda. The research team then recorded temperature and humidity data over an extended period. Their evaluations showed that temperatures fell by 9.2 degrees Celsius (average over four months) beneath the roof of a factory and by 2.3 degrees Celsius in the factory interior after the roof was painted white. The research team is happy with the results. For Dr Albert Adibekyan from PTB, this is just the starting point for intensive research: ‘The effect of passive radiative cooling is undisputed. In the next step, we want to find out exactly what influence the additional “cooling channel” through the infrared atmospheric window has.’ Adibekyan will also be taking a close look at the paint itself: ‘We want to find out how durable the paint and its properties are in the long term and how we might be able to improve this.’

Ambitious plans for the future

BGA lobbied for wider use of the smart paint at the German-African Business Summit (GABS) in December 2024. All those involved are now focusing on expanding the project further. This includes developing a training programme for skilled workers from developing countries and emerging economies. It is particularly important to the project managers at BGA and PTB that the paint is produced by local manufacturers. In South Africa, the bright white paint is to be sourced in future from a company called Splash. Its CEO, Bonga Masoka, is convinced of the project’s value. ‘The Cool White project is proof of how innovative coatings can redefine comfort and sustainability in Africa,’ he says. For Masoka, projects like Cool White help the continent at several levels: ‘Rising temperatures in Africa are not just a climate crisis but also an education crisis, as they create intolerable learning conditions that contribute to young people dropping out of school. As simple as putting a coat of white paint on a roof may sound, its impacts are decisive for building a cooler, more sustainable and more equitable future.’

Published on